Previously in the Vines Inquiry— Frank Vines arrived on Carlisle Island, the hometown he swore never to return to, only to get stuck there as a blizzard rolls across the bay.

After, Frank had run away hard enough to crack the Earth open behind him. So no one could follow. So he couldn’t find his own way back.

He looked around and saw that Carlisle, his home, had become a foreign entity. He’d forsaken the land, sold his stock, left the bramble-strewn island to rot. How dare it flourish without him? What perversion had made Lillian’s, the dive that survived on a knife’s edge, busy? He felt like a tourist, an explorer. Had he brought a plague with him? Did he want to?

Carlisle greeted him nonetheless, perhaps only because of their shared experience. For just as Frank had left the nine-point-three square miles of rock behind but still demanded a vote, he too was hounded by an obstinate Vines who wanted a say in how he behaved.

Frank turned away from the path as the trolley kicked off again, heading down the opposite side of the island. Two kids, just on the cusp of not believing in Santa, saw him and screamed. They burst from the woods and sprinted for the tram. Hopping on the rear bumper, they hitched a trip downtown with their sneakers thumping along the railroad ties. They stared Frank down with deadly glowers. He waved back and winced as the smell of winter nipped his nose.

Just on the other side of the tree line (and up a short brick staircase that Frank couldn’t count the number of times he’d swept) was a spiked iron gate, slightly ajar.

“That won’t do,” he said, echoing his mother’s oft-repeated admonishment. A short knife of a sharp life. In his day there had been a lock, but now he figured that may have been more to keep Dick from having friends over after curfew than any vandal. It had never stopped them: the Vines boys. The twins.

Frank could remember many-a-morning spent shuttling trash bags full of red cups through Vines Manor’s winding, insulated halls. Giggling while Dick tried to explain away bikini bottoms their father found in the pool filter. Frank laughed at the memory and slipped in his joy.

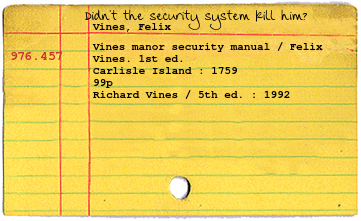

He landed on something hard and burning cold that sent a shock into his palm. Which of his parents’ unusual security measures had gotten him. A viper? The world’s smallest bear trap? Instead, he found a cold mass of black chain. Painted to match the gate, it could have just as easily been a snake, but those rarely came with padlocks. This one was still bound up in the thick links, gripping either free end.

“What happened to you?” Frank ran the metal through numb fingers. He made it to an end and a decisive, sharp edge. “Cut. Why would my parents cut you?”

The footprints in the snow didn’t have any theories, though Frank did wonder how his parents would make the broken—no, cut—chain his fault. He felt a twinge silly falling back into these old patterns; all the pondering. But that was quickly overtaken by the Vines family motto: No stupid questions.

Of course, the motto was a harder sell when he could answer his own inquiry so easily. Why would his parents cut their gate chain?

“They wouldn’t.” And that’s when Frank started running.

A car crash. On their way up the island. The roads were scraggly at best and as serpentine as the catacombs beneath Paris. He could see it. An automotive bonfire to match the gas-burning torches that lit the gravel path up towards Vines Manor. The Big House.

Frozen leaves stuck to the path, stuck to his parents’ charred faces. Mouths stretched wide and calling for him. Calling for help. Right as he was complaining about them. Right as he was being selfish yet again.

Had they driven? Frank didn’t know, because he hadn’t even walked them to their car or the trolley. He hadn’t insisted.

He rushed to the front stoop, a few square feet of grey flagstone covered by a shingle roof and flanked by twin ivy-snared columns. It matched the family crest. The wax seal on letters that came from cousins overseas.

Frank paused at the decorated front doors, his breath showing in blinking red and green string lights. Twin wreaths (that would hold another Woe sign perfectly) hung on the double doors. In one, Rosalind had nestled Dick’s favorite childhood ornament: a glass orb he’d painted a blue crab onto. (It was a frustratingly good rendering for a six-year-old). Frank reached for the doorknob and felt a hot wind on his face.

The whole manor, a ravenous mouth to Hawthorne’s ‘great human heart,’ pressed down on him. It felt like it was trolling him, daring him to enter while threatening to bury him alive the second he stepped through the front door. There were stairways he’d never descended. Hallways he was sure he’d only been in once. Frank knew the house had secrets; and he knew he did not know them all.

He raised a fist and held it by the center spine of the double doors. Should he knock? But this was his house…right?

A dense wood of pine trees whispered at his back. You’ll let them die, too?

The foyer was as he remembered. Consistently massive, the manor’s great tongue. Frank realized he was crouched. An old reflex; like he was trying to be a smaller bite for the house to chew. He stood, crouched, stood again. All the while, blood pumped so loud through his ears, it deafened any might-be screams.

He walked in, unable to answer the question at hand: Is it better to be swallowed by your past or to crawl back into it, contrite? A frigid gust slammed the door closed behind him, leaving a few twirling snowflakes to land on his stooped shoulders. The maw took him in, sampled his bouquet as portraits of ancestors sneered from gilded frames. Threads of gold inlaid into the green silk wallpaper glumly reflected the light of a single, dim chandelier.

“Just one,” a woeful Richard would say.

Frank looked around for a weapon, but found only artfully-placed show furniture—an overstuffed leather reading chair, a blue crushed velvet chaise. Eyes-only features. There was an umbrella stand, but that had as much potential to become an exercise in prop comedy as it had in protecting him and the family. Where was the family?

He picked up an umbrella anyway, hoisted it over one shoulder like the world’s gayest baseball bat and crept through the foyer. His shoes dripped on the freshly-polished wood floors until his steps were muted by a Persian rug that smelled like industry-grade detergent. They used the same kind in the hotel Frank managed.

In the center of the rug and the room, a round marble table with a seasonal display stood ready and waiting to be enjoyed from arm’s length; as was the Vines tradition for décor and affection. Frank passed one room on either side, with their archways that invited viewers like store windows. An encouragement to observe the Vines’ best selves, during business hours.

Not like the rest of the house, with its sturdy swinging doors and no keyholes to peer through. He went through one of these, cattycorner from the staircase that hugged one wall.

A door that led deeper into the manor.